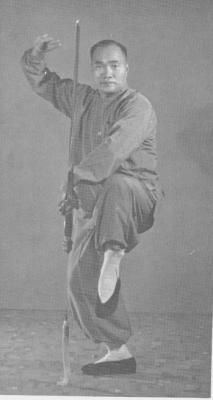

Huang Sheng-Shyan

Huang Sheng-Shyan was born in 1910 in Minhou County of the Fujian province in Mainland China.

At the age of 14 he began his life-long career into the ‘Martial Arts’ by learning Fujian White

Crane from Xie Zhong-Xian, in which he first became renowned. In 1947 he resettled in Taiwan where

he became a disciple of Cheng Man-Ching. Yang Cheng-Fu as the grandson of the Yang style founder

had been Cheng Man-Ching’s teacher. It was into this tradition that Master Huang committed himself

for the next 45 years.

At Grand Master Cheng Man Ch’ings injunction Master Huang immigrated to Singapore in 1956 and

then in the 60’s moved to Malaysia with the expressed purpose of propagating the Art of Taijiquan.

Grand Master Huang set up home in Kuching on the Island of Borneo. There he remained for most of

the rest of his life, steadily practicing, teaching, experimenting, developing his training system

and opening new schools as well trained instructors became available.

Grandmaster Huang repeatedly said that “the essence of Taiji is in the Form”, which is the set

of movements developed as a means to train the body to move in a synchronized and harmonious Taiji

manner, and that eventually every movement contains the 'Principles', and the Form becomes formless.

The practice of Taiji is not performing posture 'A' and posture ‘B', it is whether you understand

the transition from posture 'A' to posture 'B'. Attention needs to be paid to the sequence of

synchronizing, the timing and body alignment within every movement of the Taiji Form. If all of these

can be achieved than the relaxed force will naturally be cultivated - from the Form. In learning the

Taiji Form we must first emphasize the accuracies of the external postures and movements. Then we work

on the internal 'relaxation', ‘sinking', and 'grounding' before the releasing of the rebounding force

is possible. In the later stages the external and internal needs to be synchronized together.

Relaxation in the Form is produced by mind 'awareness'. We all begin with 'regional' awareness where

you move your mind to different parts of the body and visualize them to relax. After a while then when

you think of relaxing the whole body will relax as one unit. But if you only work on relaxing the body,

you are not likely to develop grounding without which there cannot be any rebounding force. So we next

need to work on 'sinking', which is a mental process where-by you guide the melting sensations of relaxing,

into the ground. The rebounding force is a product of the sinking.

Pushing-hands is an extension of the Form where you work towards remaining synchronized, balanced

and grounded even with an external forces affecting you. It works on the principle of yielding to an

oncoming force, and redirecting back to its source.

In Pushing-hands the practitioner learns to listen to the oncoming force of their opponent, stick and

adhere to him or her, follow them back until they loose their centre, then issuing the relaxed force.

"The way that you do the form will result in the way that you push hands". "By understanding yourself

and understanding your opponent, you will excel in pushing-hands." Therefore the way you move your body

and synchronize your movements in the pushing hands must be the same way as in the Taiji Form. Listening

begins in the Form, where-by you cultivate the 'understanding of yourself' and how your body moves and

synchronizes. From this you can extend your listening cultivation into the Pushing-hands to 'understand

your opponent'.

Training Pushing-hands begins with fixed pattern routines in which the body learns to respond to an

external force that has a controlled direction and velocity. As per the Form, every movement must contain

sticking, adhering, listening, neutralizing and issuing. We must be careful not to lapse into a mechanical

movement of just 'going through the motions'. The listening should develop to include not only listening

to the incoming force but also listening also to your reaction to the force, your movement in relation to

your relaxation, how you push your opponent and their reaction to your push.

Grandmaster Huang would remind students that “yielding is not running away from the force, or even

just going with the flow”. The 'Classics' state that “when a fly alights it sets you in motion”, not

that you pull away because the fly lands. What that means is that the incoming force that ‘sets our body

in motion’, just like a sponge that absorbs all of the push and returns as the push withdraws.

At the age of 60 Grand Master Huang Sheng-Shyan again demonstrated his abilities in Taiji by defeating

Liao Kuang-Cheng, the Asian champion wrestler, 26 throws to 0, in a fund raising event in Kuching Malaysia.

When teaching, Grandmaster Huang would repeatedly pointed out that; “slow is fast and fast is slow”,

to students eager to learn the Form in as short a time as possible. Those who paid no attention to this

and rushed on to Pushing-hands classes often found the need to return to the beginners and start again,

as they in their haste they had forgone accuracies. “Seek the quality not the quantity” was another

frequent saying, encouraging the students to get one movement right before moving on to the next. Not many

people like to spend a lot of time just learning one movement, and few teachers are prepared to teach the

details of one movement. The basics might seem dull and monotonous, but future progress will depend on a

sound foundation. “If you have a foundation deep enough for three stories, you can only build a three story

building. For a twenty story building you need to have laid a foundation to support twenty stories.”

Everyone has a different understanding, and a different way of delivering Taiji teachings, but that as

long as it adheres to the ‘Principles’ then it is correct. Learning Taiji is an ongoing process, so always

with the attitude of always being a student, you can continue to refine your Taiji until the day you die.

Even if you live to be over 100 years old.

True to this sentiment Grandmaster Huang Sheng-Shyan, developed his 'Art' right up until his death in

December 1992, at the age of 82.